This article by John Mansfield, MI’s Global Lead on remuneration, first appeared on South Africa’s ‘Business Day’

This article by John Mansfield, MI’s Global Lead on remuneration, first appeared on South Africa’s ‘Business Day’

Let’s not blame directors for not fulfilling their fiduciary duties and causing corporate failure. It’s not really their fault; they’re simply playing by the rules.

Our directors and managers live by a shareholder-centric governance model that forces them to behave in a certain way. They believe that maximising shareholder value is the number one priority of boards and managers. Shareholders are “owners” and boards and managers are “agents”.

They accept as true that shareholders own the corporation and, by virtue of their status as owners, have ultimate authority over its activities and may legitimately demand that the board and management, as agents, conduct corporate activities in accordance with their wishes. This notion is otherwise known as agency theory or the agency model of corporate governance and is now seen as the root cause of most corporate failures — and for the global financial crisis of 2008.

Milton Friedman spawned the theory in 1970 and Michael Jensen and William Meckling defined it in Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behaviour, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure published in the Journal of Financial Economics in 1976.

It is said that when a bad idea makes some people a lot of money, the idea catches on and becomes conventional wisdom. This is what has happened with agency theory.

Shareholders have made a lot of money through the notion and have therefore kept it in play.

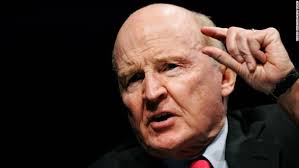

When Jack Welch was CEO of General Electric, he was held up as the exemplar of maximising shareholder value because he played the numbers game so well. He never missed his numbers and so became the darling of Wall Street and was finally acclaimed as Manager of the Century in 1999.

However, the “value” he created at General Electric proved not to be sustainable and within 10 years of his leaving, the company lost 60% of its market capitalisation. Of more interest in this context, however, is that Welch has since become the most vocal critic of the maxim he lived by.

He is now famously quoted as saying that, “maximising shareholder value is the dumbest idea in the world”.

What exactly makes the agency model so bad? It seems to revolve around the role of shareholders.

Since 1976, shareholders have somehow managed to usurp the mantle of “owners” of corporations and this claim turns out to be flawed from a practical and legal perspective.

On a practical level, ownership of an asset customarily goes hand-in-hand with responsibility. Should the purchaser of an asset choose to fund its acquisition through debt, the new owner is understood to be responsible for that debt.

Not so with shareholders. In the event that serious problems arise in a corporate, debt or otherwise, shareholders have the right to dispose of their shares and move on. They are not held accountable for the debt or for the advice they give.

Since responsibility and accountability comprise an essential attribute of ownership — and this element does not apply to shareholders — they do not meet the practical criteria for ownership.

From a legal point of view, the rights of ownership do not appear to have been specifically granted to shareholders anywhere. What shareholders do own is shares and this gives them certain rights and privileges. These include the right to sell shares and vote on matters such as the election of directors, amendments to the corporate charter and the sale of corporate assets.

The notion of ownership has caused another problem. Since 1976, the granting of shares to directors and management to align their interest with those of shareholder, has reached staggering proportions. In the US, about 62% of executive pay is in the form of equity compared with 19% in 1980.

The hope has always been that by giving executives “skin in the game”, boards and managers would behave more like owners and so improve the real performance of their companies.

As it turns out, corporate performance has declined over this period and the relationship is inversely correlated.

Harvard professors Joseph Bower and Lynn Paine have developed a new theory of the firm and named it the company-centred model.

It is specifically intended to replace the agency model, and was published in the May-June Harvard Business Review in an article, The Error at the Heart of Corporate Leadership. “The time has come to challenge the agency-based model of corporate governance. Its mantra of maximising shareholder value is distracting companies and their leaders from the innovation, strategic renewal and investment in the future that require their attention,” they write.

“A better model, we submit would have at its core the health of the enterprise rather than near-term returns to its shareholders. Such a model would start by recognising that corporations are independent entities endowed by law with the potential for indefinite life.”

The message is clear: the health of the economic system depends on getting the role of the shareholder right. If we want our boards and managers to perform their fiduciary duties, we simply have to provide them with a governance model that makes this possible.

What would it take to make the shift?

Adopt a company-centred model and develop a new set of long-term metrics that measure corporate health.

A contract between asset managers and business should also be developed to employ predominantly long-term metrics in their valuations and reports. And the interests of other stakeholders must be aligned with the long-term goals of the corporation.

John Mansfield manages the consulting practice Remuneration Management Services

Comments are closed